- This event has passed.

Lisa Oppenheim: The Eternal Substitute

“Think of depicting a zone of the heavens on a single roll of sensitive gelatin, then rolling it up like the scrolls of ancient libraries for future reference.” – From an advertorial in the Rochester Evening Times by Eastman Kodak announcing the introduction of celluloid roll film on July 11, 1889.

***

Tanya Bonakdar Gallery is pleased to present Lisa Oppenheim: The Eternal Substitute, on view from January 18 through March 21, 2020. This will be the artist’s first solo exhibition on the West Coast and her third solo exhibition with Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

As we enter the third decade of the 21st century, photographic images have never been more ubiquitous, nor ephemeral, intangible, and momentary. While the ‘instant’ is celebrated, circulated and amplified, the material objects and artifacts that define and comprise the archive, and thereby history, are in peril. For more than 15 years, Lisa Oppenheim has explored the inextricable relationship between history and photography. Establishing a practice deeply grounded in research, Oppenheim explores the materials and processes that create images, and thereby that quite literally frame the way we see the world.

Throughout the exhibition, Oppenheim presents four new bodies of work that explore celluloid film, the foundational medium that revolutionized commercial photography and made motion pictures possible. The exhibition unravels an elegiac narrative of beauty, reflection, and spectacular obsolescence, investigating the crucial role that materials play in history and cultural development.

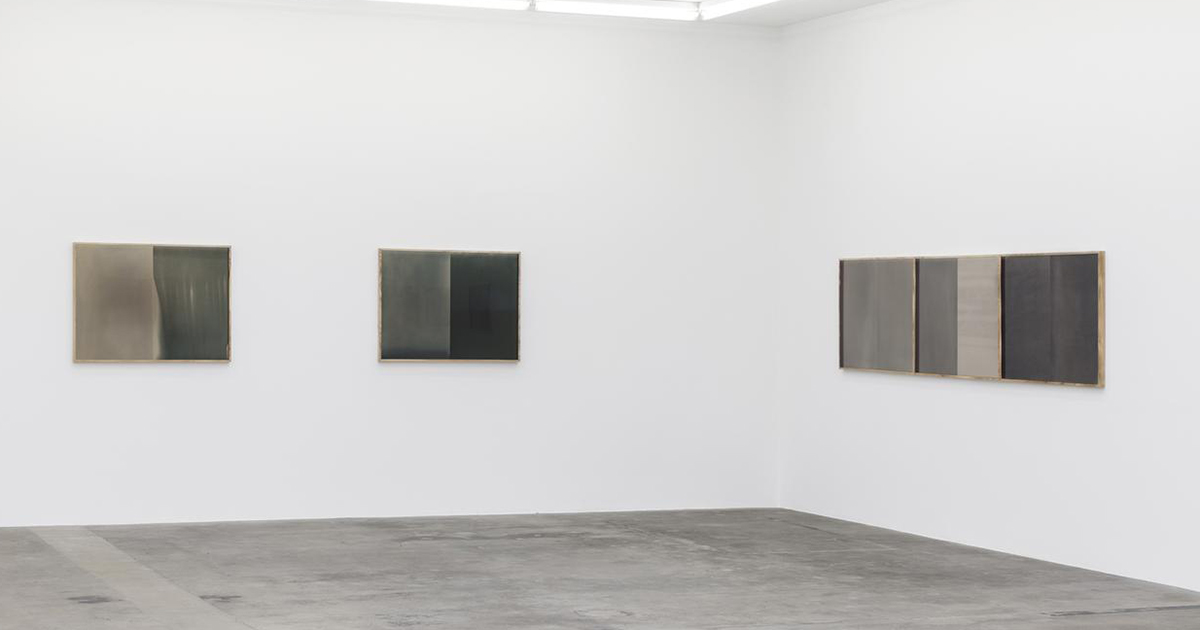

Large silver-toned photograms span the main gallery space. Using neutral density filters as a stand-in for the weightless transparency of celluloid, Oppenheim varied the exposure of each photosensitive surface and replaced the silver gelatin emulsion with metallic silver during the developing process, making oblique reference to both the “silver screen” and to photography’s limitless capacity to reflect the world back upon itself. Paired together within each frame, the dimensions of each sheet conform to the aspect ratio for still images (2:3) and as a set comprise that for silent motion picture film (4:3), which is referenced in the series’ title: 4:3:2. Using camphor wood frames, the artist underscores the relationship between the primary materials that constitute celluloid film.

First popularized in the late 19th century as an inexpensive substitute for a vast spectrum of materials from precious ivory to household linen, celluloid inaugurated the modern era of synthetic plastics. It replaced jewelry, children’s toys, toothbrush handles, playing cards and even textiles, but remained just that: an inessential alternative for common and luxury goods alike. It was not until the introduction of celluloid roll film by Eastman Kodak in 1889 that celluloid became a medium in its own right and ushered in a new era of standardization in the photographic industry.

Earlier photographic emulsions required the support of cumbersome glass plate negatives; once distilled crystals from camphor wood were employed as a plasticizing agent, the highly flexible support allowed lightweight film stocks to flicker through motion picture cameras. For the first time, images on film could be standardized and mass produced, and celluloid quickly became a metonym for the medium itself. Celluloid was eventually abandoned due to its extreme flammability but, much like the “silver screen,” its association with cinema endured even into the digital age.

In the back gallery space, Oppenheim expands her Landscape Portrait series: photograms created using paper-thin slices of wood as “negatives” applied directly to a photosensitive surface. In each portrait of the internal landscape of a given tree species— in this case, camphor— patterns emerge and resemble Rorschach tests, psychedelic patterns, or otherworldly topologies. In a near sculptural consideration of material, the wood portrayed in each image is reiterated in the frame itself—as camphor is represented in the photograph, the part of the frame surrounding it is made of reclaimed camphor wood— fusing notions of the photographic image, its substrate and material support.

For the front gallery space, Oppenheim created new works from her iconic Smoke series to signify celluloid’s ultimate downfall. The same combination of camphor and liquefied nitrocellulose that made it so successful as film also led it to combust over time. In this series, the artist crops found photos of fires or explosions and solarizes the prints by exposing them with the light of an open flame, marrying the subject with means of production: images of smoke, exposed by the light of the fire. The works’ title, Photograph of Nitrate Film Vault Test, Beltsville Maryland, was taken from the caption accompanying the archive image Oppenheim sourced from The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. As nitrate film fires became a known hazard, various agencies pursued safe storage methods in order not to lose entire inventories and archives, and explosive field tests were carried out to determine the extent of their stability. In Oppenheim’s abstraction, celluloid’s disappearance is both reinforced and reversed. A record of its imminent extinction— now absence— is materialized in the present.

On the same day that Kodak announced its release of celluloid roll film, skilled workers at the Harvard Observatory called “computers”— women who processed astronomical data — annotated star maps of the southern hemisphere. For the new series displayed in the gallery’s reception space, Computers’ Notations, July 11, 1889, Oppenheim created unique silver toned gelatin prints from images in Harvard’s archive, cropping and enlarging the Computers’ freehand markings — quick circles around stars and exclamatory arrows indicating a discovery of variation in color, brightness or position from new Observatory photographs. The superimposition of an antique-looking surface with contemporary handwritten markings blurs the viewer’s understanding of time in a manner that is typical in Oppenheim’s practice, in which she translates historical material through contemporary processes. In Oppenheim’s own translations, she performs a similar gesture to the Computers’: processing data from the infinite digital universe and distilling it to a single moment.

Oppenheim’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Museum of Contemporary Art Denver (2017), Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland (2016), FRAC Champagne-Ardenne (2015), Kunstverein in Hamburg (2014), Grazer Kunstverein, (2014). In 2014, Oppenheim was the recipient the AIMIA|AGO Photography Prize from the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Shpilman International Photography Prize from the Israel Museum. Notable group exhibitions including Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography, The Getty Center, Los Angeles (2015), Photo-Poetics, Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle, Berlin and Guggenheim Museum, New York (2015), AIMIA|AGO Photography Prize Exhibition, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (2014), and New Photography at The Museum of Modern Art (2013).

Oppenheim’s work is held in the permanent collections of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Museum of Modern Art, New York, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio and MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, Milwaukee Art Museum, among others.